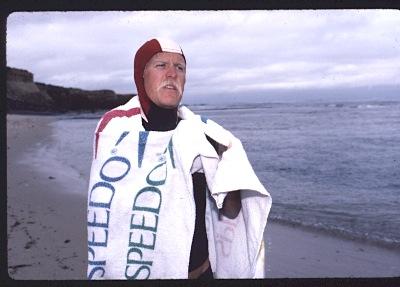

It was a cold December day in 1982 when Dave Epperson snapped this image of me in wetsuit #0000001. The Speedo towel was a sponsor-required prop

Robert Scott is on the phone. His voice is choppy and laced with emotion. He has something to tell me, he claims, that will change the future of triathlon. But the dramatic pauses get in the way of his telling.

"I read about the Malibu race."

Long pause.

"Must have been tough."

Long pause.

"I know how to keep you guys warm in the water."

And then, over the next forty five minutes, Robert "Bob" Scott explained on that November day in 1982 that he was a forty one year-old budding cyclist who enjoyed running and who never cared that much for the water. For nearly a decade, Scott had been designing wetsuits for O'Neill out of their Santa Cruz, Calif. factory. And he was now smitten by the multisport phenomenon. "Functional wetsuits altered the sport of surfing forever," Scott gushed, "and I think I can make a suit to help swimmers stay warm...forever."

Open water swimming was not a popular fitness choice in the late 70s and early 80s. Frolicking in rivers, lakes, and seas was reserved for a hot August noon and southern climes. The comfort of indoor chlorine kept the aquaticos in motion the rest of the year. Core competitors and organizers of open water swimming forbade "any type of device, worn or otherwise adorned" that would sustain artificial warm or God forbid, aid flotation. They knew that fat floated. And insulated well.

But the growing popularity of triathlons challenged a number of ancient bureaucratic barriers to performance. The question of swim-specific wetsuits simply stood in line with aero helmets, clipless pedals, and the sexiness of spandex. Why couldn't there be a wetsuit made just for swimming? Not a re-purposed surf or waterski suit but a nimble garment made of neoprene and nylon that wouldn't bind in the arms or fill with water like rubber trench coat? Lots of people had thought about the "if". And I'd imagine more than a handful pondered the "how". But the history of the triathlon wetsuit is about those who made the "when".

Like many inventor/designers, Robert Scott needed a test pilot who could challenge the products that sprung from his drafting table. Ten days after our initial call, two prototypes from O'Neill Wetsuits arrived at my door. Both were 2mm vests because, as Bob argued, "Swimmers lose more heat from their upper bodies than their legs." One of the suits had an integrated hood--one of my quirky suggestions gleaned from diving suits—and was shorn with nylon on the outside for durability. The other was high neck and hoodless with smooth neoprene exterior. I tried them both in the pool and the ocean. They were awful.

When Bob Scott called back for the report I didn't have the heart to tell him they worked like a tea bag.

"You are on to something, Bob," I offered. "I don't think I was as cold" and stopped short of telling him that I stayed warmer in the suits before and after the swim. His enthusiasm was just so infectious. I wouldn't say the suits sucked.

"What would you change?" His voice raising an octave.

"I don't know. Maybe a tighter fit. Maybe add some coverage of the, uh...genitalia."

"Yeah, I've had a change in mind on that. My hunch is that you can use a lot of heat through the boys."

The next week I wore the suit in a photo shoot for my first real sponsor, Speedo. They had paid me $500 in 1982 to schlepp the brand, but were initially concerned about how wetsuit use might affect their domination of the swim suit market. Never a marketer, Bob Scott wasn't impressed with the publicity.

"I found some new material," he re-directed. "Real NASA stuff. Buttery rubber. Gonna splice it into the arm panels."

By the spring of 1983, O'Neill's Project Tri had fostered nearly a dozen prototypes with each improving on capabilities to warm. Flotation and speed were only considered in context of warmth and flexibility. Before 1983, I don't remember ever thinking that a swim-specific wetsuit would lower times.

The O'Neill folks were looking for some kind of return on investment. Or at least a vehicle to justify the prototyping of Bob Scott. In a design setback, perhaps corporate influenced, O'Neill Inc. offered to provide free wetsuits to every entrant of the first branded Ironman race on contiguous American soil—the May, 1983 Ricoh Ironman Los Angeles, CA. There was an early season south swell and upwelling had dropped water temps to the low 60s, doable enough for the under one hour competitors, challenging for the rest. The suits provided inside the 300 competitor's goody bags were a 1.5mm, short sleeve top with a 1mm rubbery patch sewn into shoulder gussets. I'm pretty sure they were one of O'Neill's inline surfing–spec'd products. For the stronger athletes, they didn't function well as a swimming suit and roughly 50 percent of the field opted not to use them. But they kept the field warm while they waited for the start on the beach.

Bob Scott was confused with O'Neill's decision but marched on with his design nonetheless. For the progenitors of the world, it's not what is left on the cutting room floor but what ends up on the shelves. In the summer of 1983 he began sending me long-john suits with high necks. They worked better with a hint of hydrodynamic efficiency, but were tough to take off. I used the suit in a handful of cold water triathlons with encouraging results. Notably, I wore the O'Neill long-john at the Cascade Lakes Triathlon in June of that year, a high altitude event with an alpine lake swim outside the former logging town of Bend, Oregon. Water temps in the mid to high 50s. Air temps at the start in the middle forties. Fuck, it was cold!

But the tea bag was gone, the warmth was obvious, and the hint of performance increase hung in the sub-arctic air. As a middle pack swimmer, I won the race and the rest of the pros wanted Robert Scott's direct line.

In the spring of 1984, O'Neill was happy with their long-john design and had hiked up the legs to a mid –calf level in an effort to facilitate quick transitions. They decided to take them to market, but not surprisingly, couldn't find many places to sell. There were precious few triathlon stores in those pre-internet days and the O'Neill sales reps had a hard time convincing their surf, water ski, or dive accounts to carry the "new swim-specific suit." The future of mass availability in triathlon suits looked dim.

In disparate parts of the world, the summer of 1984 would be the beginning of the Age of Warmth and Flotation. Self-proclaimed endurance tinkerer Dan Empfield was no doubt dreaming of something better. And as a participant in the 1981 Hawaiian Ironman, he realized that the sport was growing faster than its science and technology. But as a mulitsport sport junkie in his mid twenties, he simply wasn't ready to get serious with his ideas; to be the entrepreneur he would become. Empfield was still tramping around the world with his bike and running shoes.

The wetsuit manufacturer, Body Glove, originally based in El Segundo, CA, and self-proclaimed founders of "the first practical wetsuit," began dabbling in swim-specific suits. Though only a handful were actually produced before 1985, the corporate wheels were turning. Guys would show up at events wearing either a long-john designed for surfing or some kind of custom suit they had altered to fit their needs. But they were rare and mostly unheralded one-offs.

Still, the mass appeal, if not the industry-specific, concerns were warmth, not speed.

In doing a sport's history it is fascinating to witness the emergence of progenitors—those unsung teachers and testers, inventors and innovators—who might've let their past contributions to the present go heralded. But there are individuals in the periphery who should hail: Hey, now just wait a minute. Because I knew a person who...and the stories move to another stem before somehow returning to the family tree. That branch of the triathlon wetsuit trunk begins with a handful of unruly Aussies from the Manly/Curl Curl Beach area north of Sydney. Part by accident and part by design, they realized that rubber floats. And properly placed on the human form, increases speed in the water.

I remember it like this: Standing on the starting line of the 3MMM Triathlon in Manly Beach, Australia on November, 11th, 1984. It was the first Ironman distance triathlon in the country of lovely convicts and even though the water was a comfortable 74 degrees F, the guys to my left and right were clad in these suits that looked just like the O'Neill long-johns. But the neck was higher, they were all smooth neoprene, and they were thick, maybe 3 to 5mm if I could've guessed. One of my hosts, the affable cad (and a lifelong matey of mine), Marc Dragan, wore one of the suits.

"C'mon, Drags," I pleaded, "what's with all the blubber? It ain't that cold, Pal."

"Sorry, Hollywood. Me and me mates get real chilled in these long swims."

And as I heard the cackling from the gallery, I knew I'd been had. The boys were in the know.

Flash back to one of those legendary Aussie surf lifesaver types, you know...started swimming at six, surfing at eight, pulled a few tourists from the rips by twelve. John Daffy started training for his first triathlon outside of Sydney in 1980. As a member of the Harbord Diggers Triathlon Team, Daffey was used to cold water swimming. But he didn't like it. And like Marc Dragan, he was never as fast as the rest of the hot-shit Aussie kids. But he had entered the 3MMM Ironman and was determined to finish.

"I realized I could not cope with cold water," he reminisces over thirty years later, "and I seemed to have a thermostat that gave me ice picks through the forehead when swimming in water below 17 degrees C (63 degrees F)." But like most of the open water swim participants, the scientific answer was acclimatization—get used to it, take a lot of cold showers, add body fat. This didn't work for Daffy, and after weeks of effort he was resigned to wearing a (what he thought would be slower) wetsuit if he wanted to finish. But in the subsequent testing of "about 20 different suits" Daffy made the discovery that size matters, at least when it comes to thickness and fit.

"My first objective was to reduce heat loss from the head, neck, and lower abdomen/groin" he recalls from his Sydney home. "But as my trials continued it was apparent that much of the drag was due to water entering via the neck, chest, and arms." Nothing new there, I thought. Bob Scott had that figured out 18 months ago. But then Daffy hit the mother lode.

"A few particular suits stood out - a 7mm or 9mm diver's suit- where my arms were worn out in less than 50 meters. But some of the trials with a short, thick, sleeveless, and very tight suit showed I was swimming faster."

Armed with his data, John Daffy marched into a local wetsuit manufacturer, Sport Skins at Manly Vale, and "gave them my specifications and selected a material." There was no material suited to make thin sleeves, he recalls, so he ordered this suit:

Sleeveless Wetsuit - 3 mm neoprene, flock lined. Long, large back zipper with Velcro stopper at neck and Velcro tag at end of zipper cord. Long legs with side zippers and Velcro stoppers. Very tight fit.

And when his training pals, Dragan, Sean Vale, Alan Mitchell, and Terry Blewitt saw his new free speed in the pool, they were next in line at Sport Skins. But only Marc Dragan made the leap to elite competition in the U.S.

One of Dragan's first great performances in the U.S. came at the President's Health Club Triathlon outside of Dallas, Texas where he finished fourth against an elite field that included Scott Molina, Dale Basescu, and a kid from down the street named Lance. On the morning of the start the air, humiodity and water temperature were all 85 degrees. It was so pleasant you wanted to turn up the AC in the hotel and go back to sleep. Marc wore his increasingly familiar black long-john on the starting line. I looked at him and sensed by then that the flotation was an ergogenic aid: it helped the weaker swimmer more than it helped the faster ones. And I was pissed that I hadn't brought home a Sport Skin sample the pervious fall or at least convinced Bob Scott to double down on thickness. One of the other pros in Dallas tried to harass Dragan about the suit but he fired back in quick Aussie fashion, "Well, it might slow me down a bit but I really do feel the cold."

The word was leaking slowly but surely. These things can improve body position in the water.

But custom suits were still just that...custom. You had to have a connection or find someone at a rubber store who could envision what you knew was advantageous. The famously slow swimmer but outstanding Dutch age group cyclist, Han Dieben, was early informed about the benefits of wetsuits. Dan Empfield recalls:

"Hans brought over a suit from Hot Designs in the mid 80s but I really only saw three of them ever used: one by Hans, another by a kid in his mid-teens who always showed at all the races with all the latest stuff, and Mike Fillipow (an early elite from LA), wore one in 1986 I think it was, in Catalina, where he was first out of the water and last out of transition because he couldn't get it off. It was front-zippered and had a built-in hood. The founder of Aquaman claims he had his suit before I had mine. Maybe that's true. I never saw one."

But what Empfield did see was a measurable performance increase with the increasingly popular swimming wetsuits. "When I saw you, and Gary Peterson, swimming Bass Lake in '86 faster than you should," he allows a shallow dig at our average swimming abilities made better with the accidental floatation, " in wetsuits that, to me, looked pretty much just like surf wetsuits, I thought, what would happen if you actually optimized a wetsuit for surface swimming?" Indeed. What would happen if you could take an average swimmer and put them in the lead pack? Or a poor swimmer with sea-anchor feet and place them mid pack, warm, and ready to ride? You'd sell a bunch.

As with anything new, the early imitations were equal parts creativity and absurdity. I can remember standing off to the side of one transition area in 1987 and watching a young man peel down his over-sized long-john only to reveal that he'd coated his entire body in bubble wrap from the Post Office. The person standing next to me started laughing hysterically. "Next thing you know," she offers, "the swimmers will hire huge guys to toss them like dwarves at the start; just skipping over the first 100 yards like a stone."

If there was a tipping point, it was in 1987 when Empfield founded Quintana Roo to produce, market, and sell sport/speed-specific wetsuits. Empfield's role in wetsuit design, development, and distribution is undeniable. Take away Dan and QR and someone else might've filled his role. But they didn't. And Empfield almost didn't.

"At the time I wasn't trying to sell anything. I was just researching an article I was going to write. I went to Victory Wetsuits, talked to the owners, Mark and Greg. Asked them if I could go in back and mess around with wetsuit designs along with their factory workers. They didn't really make anything like a tri wetsuit, but they did glue and blindstitch a 3:2 suit out of nylon two-sides. I got some rubber from a company called Rubatex, smooth one-side, they made rubber for U.S. Divers. Took it to Victory, had it glued one-side, sewn the other side. Messed around with the patterns, the neck, and the thicknesses. Made it 5mm in the body. Swam in the suit. Looked at my watch. Got another watch. Swam in it again. Decided to do more than just write an article. Started Quintana Roo."

In doing a sport's history, especially something as inane as a consideration of the first versions of a product, one necessarily must pause and wonder who really cares. There are no Pulitzer Prizes for building the first widget, even fewer for being the first to build a prototype or lie in bed and dream one. Those who had a hand in the dreaming, designing, and developing of the triathlon wetsuit have largely discounted their role, choosing instead to take the higher road in acknowledging the collective effort.

To my knowledge, no one party has laid claim to being "the one." Still, with a nod to the difference between inventors and innovators, no one person made the triathlon wetsuit more available during the late 80s and early 90s than Dan Empfield. "It doesn't matter to me," Empfield muses when thinking back on his contributions with Quintana Roo. "What I do know is that nobody wore wetsuits prior to 1987, (and) everybody wore wetsuits after 1987. All those wetsuits were QR except for your O'Neill. If you want to give it to O'Neill, that's fine. I'm not going to try to stop you."

Dan's statement is true enough but also telling in what else it asks. What about his connections to the Victory Wetsuit factory in the fall of '87? What about the post millennium efforts of the modern too-many-to name triathlon wetsuits? Haven't they contributed something to the history of safety, comfort, speed, and warmth? And why would O'Neill, the largest wetsuit company in the world cease their production and sales of triathlon wetsuits in the early 90s just before the boom?

"There are two ways you can count something as the original," Empfield reflects. "One way is to say, 'This was the first guy to think about it.' The other is to say, 'This is the first time the idea stuck.'" But ideas don't stick without successful business platforms, I pressed. "C'mon, Danny Boy, tell us more about Victory and how you really feel."

"I continued to use Victory as a contractor but they could never really build me more than about 200 suits a month, top end – they had their own production to make. I needed 1000 wetsuits a month. So, really, I think I was just the first guy to put all the features into a surface swimming wetsuit that caused the wetsuit category to catch fire."

In this respect, Danny Boy Empfield is not that different from Jim Jannard (inventor/founder of Oakley), Jim Gentes (inventor /founder of Giro Helmets), or Brian Maxwell (inventor/founder of PowerBar). Each created a sport-product category that had not been there before. They didn't invent sunglasses, bike helmets, or packaged food-bars. But they altered them enough in thought, design, development, and application that they might as well have.

"It's kind of like Look's clipless pedals," Empfield continues. "We saw Cinelli's clipless pedals in the 70s. So? Look didn't invent the clipless pedal. They just invented the design that eventually caused people to want to buy clipless pedals."

Empfield and Daffy can wax poetic about their respective roles. Where Dan muses about the value of gas-blown Rubtex rubber or Yamamoto smoothy-style, Daffy will argue that is was peer pressure and pure survival that led him to realizing the effects of slippery-sided swimming wetsuits.

Sadly, for his part, Robert "Bob" Scott never lived to see the zenith of his contributions. On July 18th of 2004, Scott was training for the Duathlon Worlds when he was hit by a bus just north of Boulder, CO. He died from his injuries. And never saw the bus.

What none of the group foresaw as well was the controversy that would surround the use of these "artificial floatation devices." As swimming wetsuits became popular in 1987, they entered the divisive world of triathlon politics. Realizing that they would help the sport grow and add a layer of needed safety, the governing bodies at first embraced them. But another vocal group of athletes (strong swimmers) who happened to be effected by their use mounted a successful campaign to limit their use to cold water swims. The problem was that no one could agree on what cold meant and few officials had reliable measuring devices or the ability to measure all parts of the course. On many an occasion, wetsuits were disallowed because TriFed officials had found that the near-shore water temp was 72 or 74 degrees F while swimmers were surprised to find 64-66-degree water on the majority of the course. It was a polarizing game that divided the elite athletes for a several years.

The new wetsuit manufacturers were concerned and sought to influence the outcome with empirical data. Athletes too, were putting the new suits through time trials with highly mixed and unreliable results. It was generally thought that the inherent floatation aided the poor swimmers more than the fast ones. But could the same be said for disc wheels and good cyclists? Lightweight racing shoes and fast runners? What about athletes who could process energy bars faster due to neutral GI tract osmolality? Eventually a fixed number was applied and the next generation of pros and age groups alike learned to live within that structure.

# # #

Marc Dragan, John Daffy, and their merry band of Aussies continue to splash about in their North Sydney playgrounds, retired, semi-retired or not really caring about the difference. Marc reminds me in a conversation that he was so cold after a swim in Tasmania, that he wore his wetsuit on the bike for nearly ten miles. He also reminds me in a classic Aussie dig, that I (unsuccessfully) wore a (very slow) 1mm short-john-style wetsuit during the swim at the Hawaiian Ironman in 1986. And Dan Empfield, after selling QR in 1995, still owns and manages the popular triathlon-related website, Slowtwitch. He is a member of the USAT Hall of Fame (2004) and was given the World Open Water Swimming Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010.

Triathlon wetsuits continue to push new boundaries in design, warm, and speed. The top brands are approaching $1000. And most of them only last a year or two before they lose some of their qualities.

Postscript: Regardless of Dan Emfield's collectivism, he will often point in jest to "the ultimate authority on the subject." Checxk out the clip: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=doTuEGm40qo

Why anyone would keep receipts for over 30 years is beyond me. But we’re glad he did. This is how history is authenticated.

John Daffy with the Daffy suit: “Wetsuit # 00000002

John Daffy in the flesh and neoprene. First Aussie IM distance race in 1984

O’Neill ad showing early version of the first full suit in 1986